Rubens: the last Renaissance painter

Peter Paul Rubens worked in the 17th century, when the Baroque was in full swing. His visual language too has all the features we associate with the word ‘Baroque’: vibrant, crowded and exuberant. And yet. Was he truly all that Baroque? Rubens expert Nico Van Hout argues that the Antwerp master was actually the last of the Renaissance painters. What does that mean? And how can we prove it?

The Roman Empire: a universal inspiration

As the Middle Ages drew to a close, the Italians were excavating one ancient sculpture and building after another. The art of the supposedly barbarian medieval era never really took hold in Italy after the Western Empire fell in 476. So it was natural for the social elite there to associate themselves with Rome’s lost imperial glory. Roman art, culture and political organization provided a model for Italy’s rebirth. From the 16th century onwards, the new arts that emerged – full of muscular men and nude Venuses – also began to attract artists from the Low Countries. Otto van Veen (1556–1629) was among those who travelled to Italy to study them on the spot: the very artist who would later be Peter Paul Rubens’ last teacher.

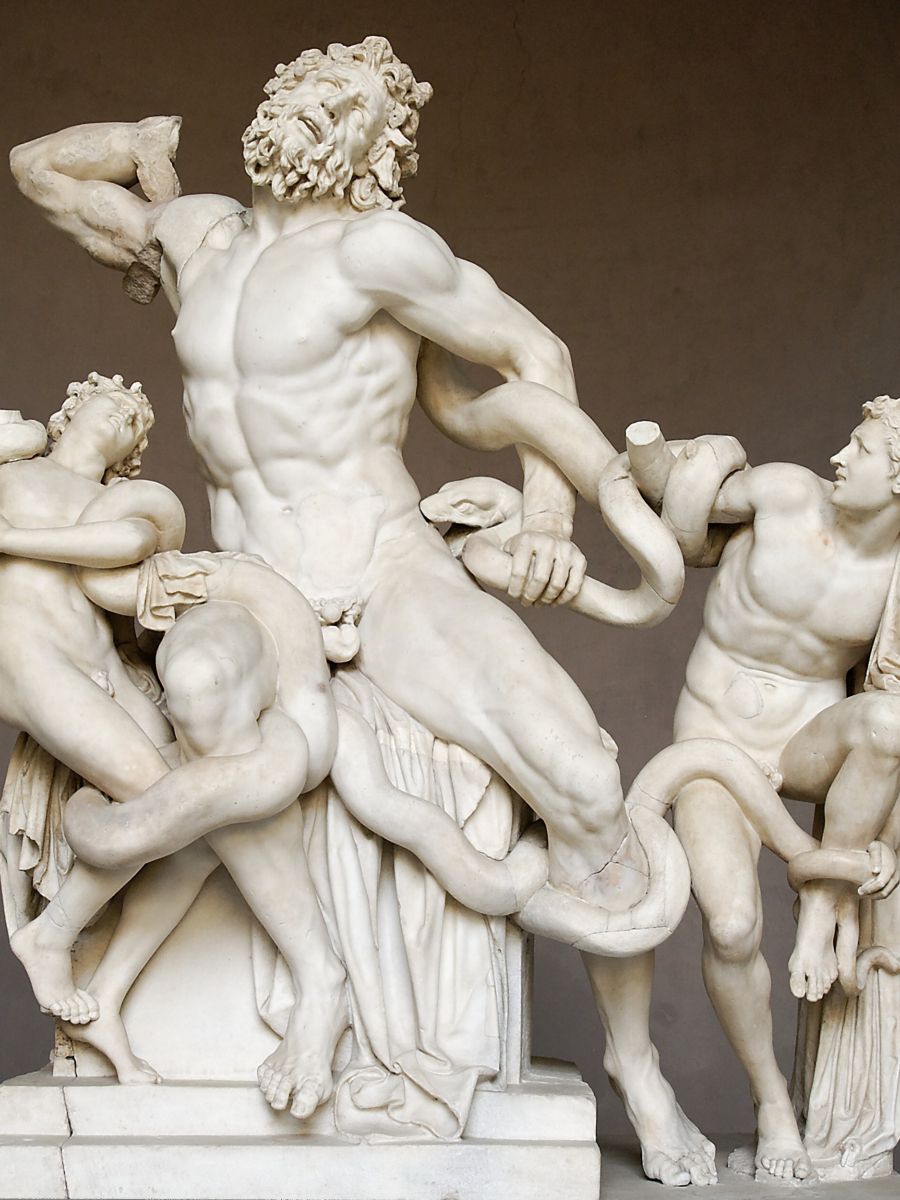

Antique muscles in the Laocoön group

The Belvedere Torso: a drawing by Rubens in the Rubens House collection.

Rubens and Italy

And what do we find? In 1600, Rubens too set off for Italy, where he would spend the next eight years. Enough time to fill sketchbooks with sculptures and friezes. And to cultivate a deep passion for antiquity, from literature to art and from coins to images carved on gemstones. Rubens began to collect as well: besides his sketchbooks, his private collection of antiquities provided an inexhaustible catalogue of motifs that he could rework to his heart’s content. All blended, of course, with the trendy Renaissance art he had seen in Italy. The work of Michelangelo and Titian, for instance, each of whom reinterpreted antique examples in his own way.

Master of transformation

Rubens didn’t copy his sources of inspiration verbatim. He incorporated them in a synthesis all of his own, with the result that each work is unmistakably a Rubens. In what amounted to a respectful competition, he constantly sought to refine and surpass both his sources and himself. In his Venus frigida, Rubens took a stone Venus, draped her with a painted hide and turned her into a goddess who is very much alive.

Unlike Vincent van Gogh, say, Rubens was not the most original artist. Yet he was unequalled when it came to reinvention. He placed classical figures in dynamic compositions that generate the most grandiose of emotions.

What links him to his beloved exemplars is the importance of the narrative. It is the compelling stories that convey the emotion rather than the individual moods of the characters. Artists around him, such as Rembrandt, Frans Hals, Adriaen Brouwer and Diego Velazquez, were more likely to show the soul of people in their portraits. That’ not something Rubens did very often, other perhaps than in the portraits of those closest to him. This is what makes him the last Renaissance painter.

Rubens saw this crouching Venus in the collection of his Italian patron Vincenzo Gonzaga in Mantua

Venus frigida in the KMSKA collection