James Ensor

James Ensor in bird's-eye view

James Ensor in bird’s-eye view - Episode 1

James Ensor was undisputedly the greatest Belgian modernist. In this episode we are going back to his roots in Ostend.

James Ensor in bird’s-eye view - Episode 2

Find out more about the creative process of the artist along with the researchers of the Ensor Research Project.

James Ensor in bird’s-eye view - Episode 3

In this final instalment, we take a closer look at the man as an artist. And we give some of his fans the chance to sing his praises.

The complete collection of paintings

The man behind the masks

To us, James Ensor was a pioneer of modern art. But who was the man behind the masks? He was a complex personality with one foot in the 19th century, the other in the 20th. Traditional and innovative at the same time. A difficult man, who nevertheless took care of his family all his life. Dignified but happy to horse around on the beach. Devoted to Ostend, but frequently found in Brussels. Ensor had many different faces.

Curiosities

James Sidney Ensor grew up in Ostend, the son of a Belgian mother and an English father. The family rented out guest rooms and ran a souvenir shop selling curiosities. Such as the grotesque carnival masks that would later feature so prominently in his paintings. Women were a favourite theme too. Which makes sense: after his father died in 1887, James took responsibility for his mother, his Aunt Mimi, who lived with them, his sister Mariette and her daughter Alexandrine.

Attic studio

Ensor caught the creative bug at an early age. He enrolled at the local drawing school and by the age of 16 was painting outdoors. His studio was set up at home in the attic. Ensor was a homebody, but he still went to Brussels to train at the academy. While there, he immersed himself in the freethinking atmosphere and got to know the printmaker Félicien Rops and the writer Eugène Demolder. They encouraged him to develop his innovative view of art.

Adam and Eve expelled from Paradise - James Ensor, KMSKA

Avant-garde

Was it because he lived in a house surrounded by women? Besides still lifes and seascapes, Ensor indisputably liked to draw portraits of young middle-class women. The Oyster Eater, for instance, is a European realist masterpiece. Ensor had an extensive social network and, together with several fellow former students from the academy, he founded Les Vingt (‘The Twenty’). The association went on to play an important role in promoting the latest movements in art.

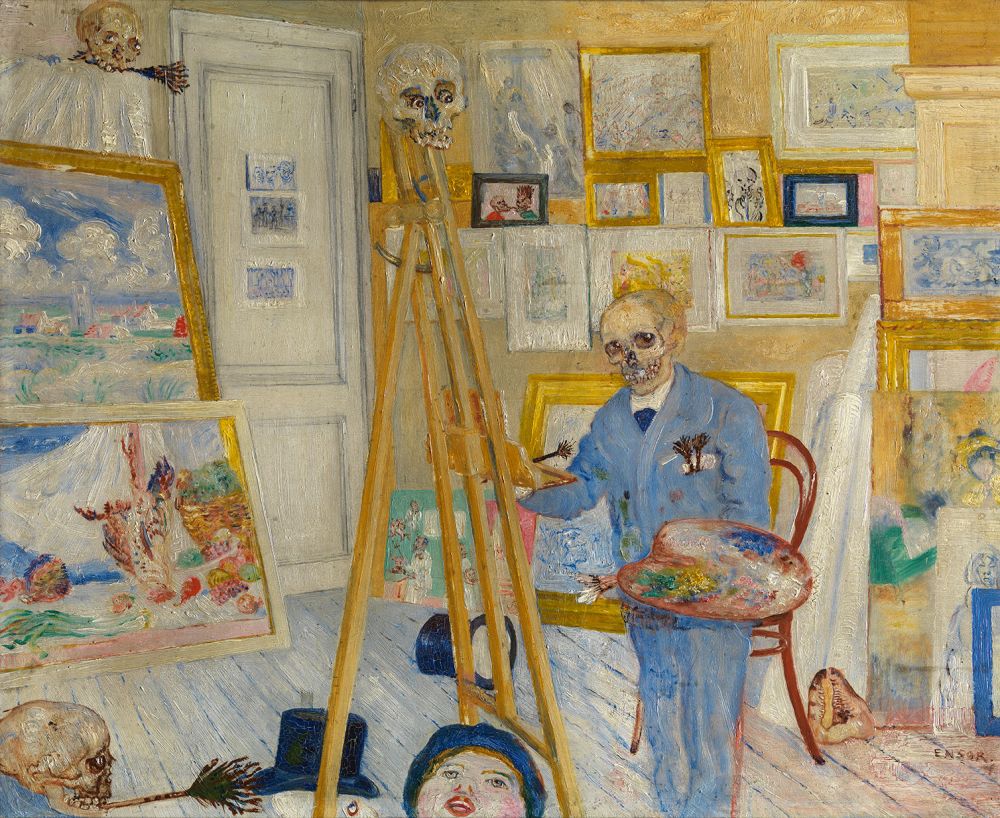

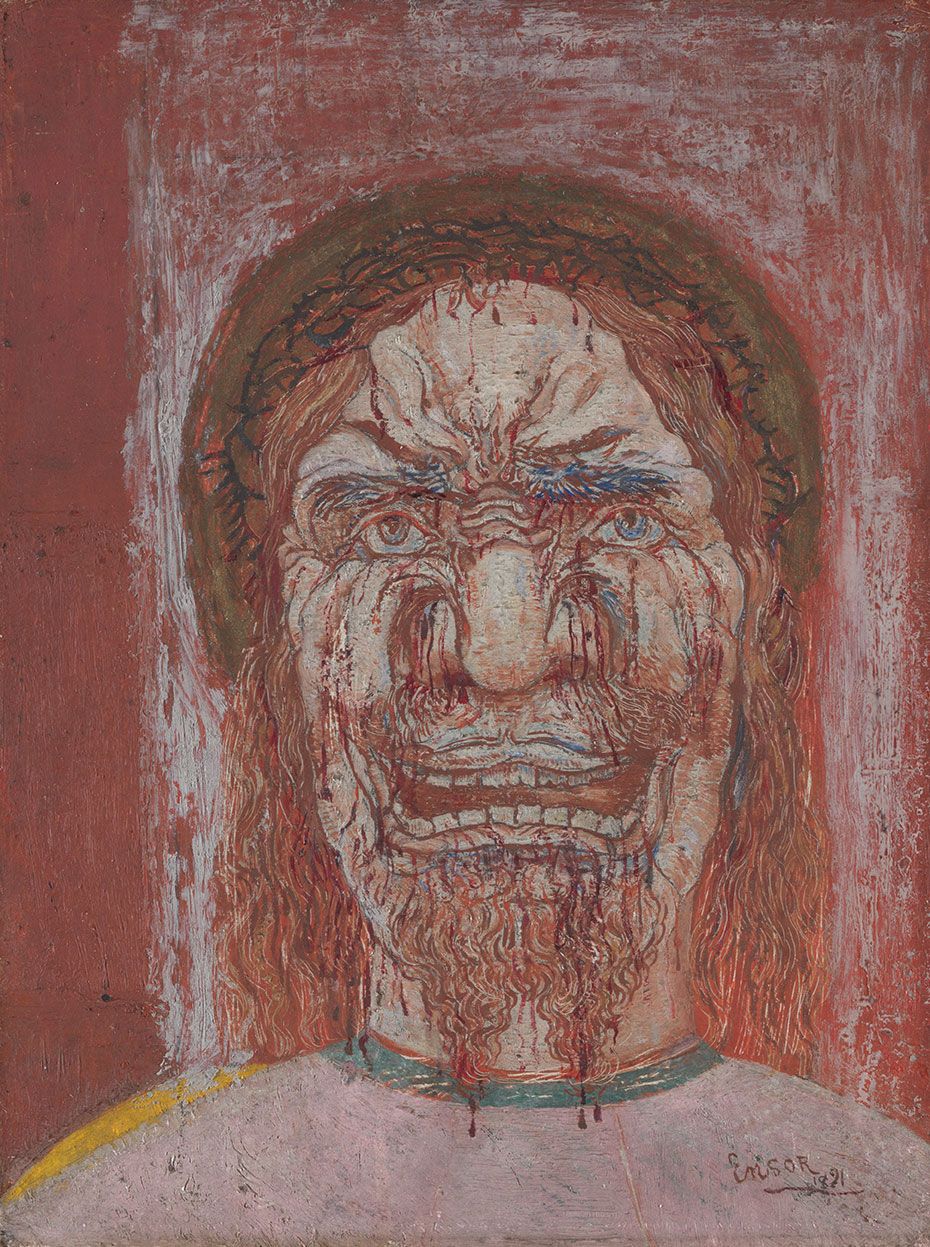

Masters and skeletons

Ensor gradually developed a visual language entirely of his own. He experimented with light, line and colour, while macabre motifs like carnival masks and skeletons began to make an appearance. The result was world-famous masquerades like The Intrigue, one of the highlights of the KMSKA collection. Ensor also made his breakthrough in Germany, where they nicknamed him Le peintre des masques. The artist Paul Klee, among others, was heavily influenced by him.

Masquerade - James Ensor, KMSKA

Antwerp

In 1905, the association Kunst van Heden (‘Art of Today’) organized a major Ensor exhibition in Antwerp. His work caused a furore and several members of the association bought paintings from the show, which they later donated to the KMSKA. The museum’s collection has grown steadily over the years. Additional donations and targeted acquisitions mean that the KMSKA now owns the largest and most diverse Ensor collection in the world.

Creative Baron

What about the artist himself? Ensor wasn’t one to sit quietly: he continued to make his voice heard until his death. He published on art, unveiled his own statue in Ostend, was a regular after-dinner speaker, wrote a libretto, composed music for a ballet for which he also designed the costumes, was granted the title of Baron and even met Albert Einstein.

On 19 November 1949, he died at the Heilig Hart hospital in his beloved Ostend. He was 89. Belgium had lost a phenomenon.