Jules Schmalzigaug

It is in Italy that Antwerp-born Jules Schmalzigaug (1882-1917) discovers the light and colours that set alight his futuristic style. His revolutionary compositions catapult him to the forefront of the avant-garde... until World War I forces him to leave for The Hague. Despite his untimely death, his innovative vision of colour and movement remains a landmark in Belgian modern art.

Schmalzigaug in the KMSKA

The KMSKA's Schmalzigaug collection has expanded thanks to purchases, donations and bequests from passionate collectors and family members. To keep Jules' artistic legacy alive, his brother Walter Malgaud donated a first selection of works to the museum as early as 1928. Later on, donations followed from Maurice Verbaet, Ronny and Jessy Van de Velde and Jean Malgaud, among others. These added not only paintings to the collection, but also drawings, sketchbooks, graphic work and personal archive documents. Thus, the KMSKA was able to develop into a research centre for promoting Schmalzigaug's position within the European avant-garde, welcoming those who wish to study the artist.

In the following we display, besides Schmalzigaug's oil paintings, a selection of works that show his growth from gifted, but somewhat traditional, draughtsman, to abstract artist looking at the world as through a kaleidoscope.

The complete painting collection

Pioneer with panache

Jules Schmalzigaug (1882-1917) is raised in an age of major change, marked by the impact of technology and speed. His artistic quest takes him from Antwerp to Germany, France and especially Italy, where he discovers the light and colours we associate with his paintings. Initially searching within tradition, he finds his own voice in Futurism. His dynamic compositions align with the avant-garde, but then World War I forces him into exile in The Hague. His tragic death in 1917 abruptly put an end to his promising career. Fortunately, his innovative vision of colour and movement lives on in Belgian modern art.

A hesitant beginning

Schmalzigaug grows up in a world in transition that fascinates him immensely. Electricity, fast means of transport and technological innovations are drastically changing life. His native Antwerp is right up to speed with the trends. As a teenager, Jules gets treated for his scoliosis in Dessau, where artist Paul Riess discovers his gift for drawing. His affluent family supports a broad art education in Belgium, Germany and France. By 1905, his formal education is complete. There is still no trace of the bustling world around him in his dark, conventional works. He is uncertain about his role in the art world and has a deep respect for traditional art, which he also sees at the KMSKA.

The Italian awakening

He is roused by a tour of Italy in 1905, and particularly enchanted by the light and atmosphere of Venice. In the Netherlands and France, he discovers new styles which appeal to him more than the conservative Belgian art world. The only Belgian artist he finds interesting is James Ensor. He writes that thanks to the Ostend light, Ensor sees ‘improbable colouristic chords’ in the most banal things. Clashing colours, blue next to red, yellow and green, pure fields of colour.

Futurist transformation

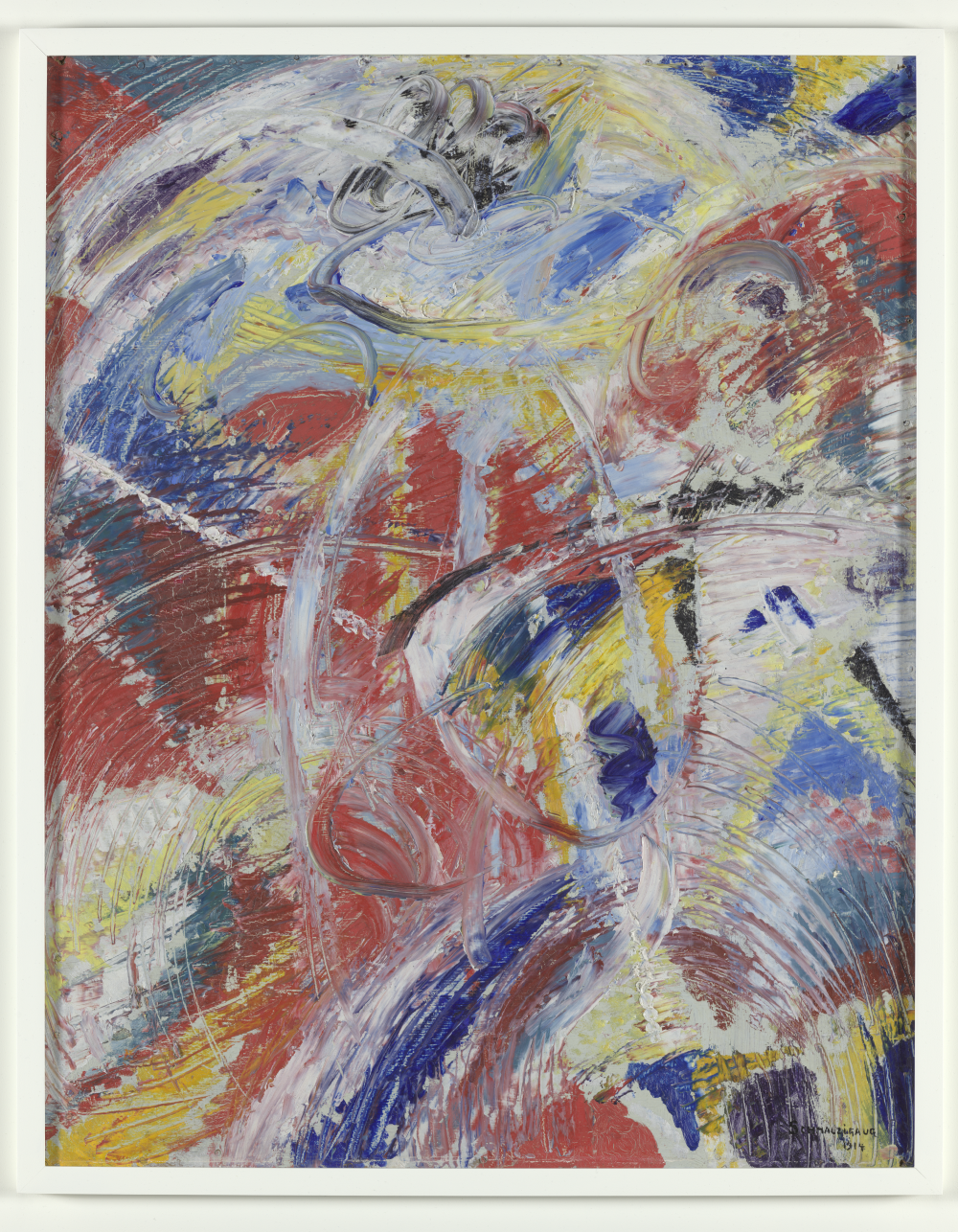

Schmalzigaug finds Paris too impersonal, yet it is there that he discovers his artistic path in 1912, after visiting an exhibition of the Italian Futurists. Inspired by Giacomo Balla and Umberto Boccioni, he embraces the movement that does know how to transform speed and energy into radical art. From Jakob Smits, he learns how light and blocks of colour can form the core of a painting. Back in his Venetian studio, he starts to decorate the studio with cloth like Smits, so that reflections of light interact with shadows. For him, colour is not an illustrative element but becomes the essence itself. His work captures the energy of dancers, the movement of crowds and the hypnotic atmosphere of modernity.

International success

In 1914, Schmalzigaug achieves his international peak through participation in the Esposizione Libera Futurista Internazionale in Rome. In his studio, he is working feverishly on paintings that not only fit within Futurism but also express his own chromatic theories. He exhibits six works that he considers sufficiently avant-garde, including Development of a Theme in Red: Carnival, the first fully abstract painting by a Belgian artist.

In dialogue with the past

Through his passion for colour, Schmalzigaug manages to link the beloved traditions of old masters with the avant-garde experiments of his time. To Boccioni, who has since become his friend, he writes: ‘I know of no Impressionist painting with such a singing red as in King Melchior's cloak on The Adoration of the Magi by Rubens.’ In Rubens, he sees no static past, but a dynamic forerunner. Rubens' repetitive swirling lines and theatrical qualities provide him with a basis for his own abstract compositions.

War and isolation

But despite his ascent in the avant-garde, Schmalzigaug remains vulnerable. World War I forces him to move to The Hague, which abruptly interrupts his career. He loses contact with Futurist companions and abandons works in Venice. In The Hague, he seeks connection with other Belgian artists in exile, such as Rik Wouters and Georges Vantongerloo, who undergo his influence. Despite the war, he remains productive, continuing to experiment with colour and light in both figurative and abstract works, from cityscapes and portraits to Futurist compositions. His unpublished treatise La Panchromie (1916) couples scientific principles with a method for applying them, inspired by Ogden Rood's theories. Schmalzigaug is clearly not only searching intuitively, but also intellectually, for a universal colour system to harmonise light and composition.

A final quest

He finds an outlet as artistic adviser at the Belgian School of Domestic Art. He teaches art history and drawing and stresses the importance of innovation. His postcard-like pastel sketches of The Hague and Scheveningen, with bridges, streets and the beach, show a more subdued style, but colour remains key.

In 1916, his work catches the attention at the Exhibition of Belgian Art at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, but reactions are mixed. Physical pain due to scoliosis and mental isolation weigh heavily on him. He is equally affected by nostalgia for Italy and the loss of avant-garde friends such as Boccioni.

An abrupt end

Schmalzigaug's suicide in 1917 abruptly ends his quest. A pioneer of Futurism, he remains a unique voice in Belgian modern art. His work exudes speed, modernity and an intense quest for a place within art. Despite his career being short, he remains a colourful pioneer within Belgian art history.