Review of the KMSKA's colonial history

In the run-up to the KMSKA’s reopening in 2022, the museum has reviewed its colonial histories. We have looked in particular at funding derived from the Congo and at the ‘human zoo’ organized on the museum square. A number of colonial narratives within the collection have also been traced. The principal findings are summarized below along with our ambitions for the future.

1. COLONIAL FUNDING

BUILT WITH BLOOD MONEY?

King Leopold II used large sums of money extracted from the Congo to fund construction projects in Belgium. Public awareness of this phenomenon has grown in recent years, with the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren (RMCA), now also known as the AfricaMuseum, as a well-known example. The RMCA was built at Leopold II’s direct behest, using funds extracted from what was then the Congo Free State.

There is a perception that the KMSKA had similar origins, but this proves not to have been the case. The two million Belgian francs required to build the museum was funded equally by the City of Antwerp and the Belgian state. The chronology of the project indicates in turn that neither city nor state obtained those funds from the Congo.

Construction of the museum was approved in 1875, commenced in 1884 and was completed in 1890. Although the Congo Free State was established in 1885, the colony did not begin to generate revenue for the Belgian occupier until demand for rubber rose in around 1895. Leopold II and Crown Prince Baudouin were given a preview of the new museum on 25 July 1890. The Belgian monarch was already responsible at that point for the brutal repression in the Congo, but the colony had yet to bring him substantial profits. The RMCA, by comparison, was constructed in 1897 and expanded in 1908–10.

COLONIAL DONATIONS TO THE COLLECTION?

The Belgian occupier viewed the Congo as conquered territory and set out to extract as much wealth as possible from the colony. This made Belgian colonial companies some of the most profitable in the world, while saddling the Congo with a heavy legacy. Leopold II involved Antwerp entrepreneurs in the colonial project from the very beginning, which means they had an early share in the profits.

Between 1815 and the present day, the collection grew from 241 to 5,500 objects via donations, bequests and purchases. Donations and bequests provided 1,742 items, representing 39% growth in the collection. The museum’s donors included several families known to have had colonial links, among them the Osterrieths, Grisars and Francks. Working with a team of experts, we evaluated which individual donors were politically active in the Congo or engaged in colonial trade before bequeathing works to the KMSKA.

Not every member of the aforementioned families can be linked to the Congo. François Franck, for instance, who donated 27 works to the museum, was active in antiques and interior decoration. Many of the families in question had also made their fortune before the beginning of the colonial period. This enabled Felix Grisar, for example, to donate two paintings in 1879, before the Congo Free State was established.

Fifty-seven works from 18 different donors were possibly or probably funded by colonial money, accounting for 3.3% of overall donations. The largest cluster comprises 16 works donated by Arthur Van Den Nest after 1895. Van Den Nest was a leading Antwerp politician and chairman of the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company (ABIR), a major player in rubber extraction, which maintained close ties with Leopold II and employed forced labour and violence in the Congo.

KMSKA SUBSIDIZED BY CONGO?

The KMSKA, which nowadays operates as an autonomous agency within the Flemish Government, was a Belgian institution during the colonial period. It was initially administered by the Belgian Ministry of Arts and Sciences (1890–32) and later the Ministry of Public Education (1932–60). The museum purchased 1,797 works via government budgets between 1890 and 1960. KMSKA staff were, moreover, employed as state civil servants from 1930 to 1960.

The Congolese treasury directly funded several Belgian colonial institutions during the period of the Belgian Congo (1908–60), including the RMCA, the Colonial Ministry in Brussels and the Colonial College and Tropical Institute. Other federal institutions like the KMSKA received subsidies from the Belgian treasury.

The weight of colonial activity within the latter is difficult to quantify, but current research suggests that it ought not to be overstated. Calculations made in the lead-up to Congolese independence estimated the colonial share within Belgian tax revenues at 3.6%. It is widely believed that the biggest colonial profits flowed to banks, corporations and private fortunes. The acquisition of works for the KMSKA was, therefore, possibly financed with money from the Congo via government subsidies, but only to a limited extent.

2. THE HUMAN ZOO ON THE MUSEUM SQUARE

The following section addresses a shameful chapter in the history of the museum square, namely the ‘human zoo’ that formed part of the 1894 World Exhibition in Antwerp. The organizers put 144 Congolese people on public display, seven of whom died as a direct consequence. We will look first at the World Exhibition and then at the KMSKA’s role in it.

BACKGROUND

World exhibitions were an international phenomenon in the second half of the 19th century. Held in several European countries, they celebrated industrialization and international trade, which was frequently accompanied by imperialism and colonization. Participating countries showed off their achievements in different sections.

Belgium hosted 11 world exhibitions between 1885 and 1958, three of them in Antwerp. The 1885 and 1894 Antwerp world exhibitions were held in the Zuid (South) district. Nowadays, the area is solidly part of the city, but at that point it was being rapidly developed. The world exhibitions were used to showcase the new district. They were organized by a specially created Public Company with close links to the Antwerp business community and the City Council.

The first of the Antwerp world exhibitions took place in 1885, the year the Congo Free State was founded. Leopold II’s employees immediately seized on the event as a propaganda tool. Commodities from the Congo were displayed in the large central exhibition hall to drum up investors. The Société Royale Belge de Géographie, founded at Leopold II’s instigation, set up a separate Congo Pavilion in which Congolese objects – for the most part looted – were exhibited. It was located on the waterfront, near the Waterpoort on Vlaamse Kaai.

The society installed a replica hut in front of the pavilion, around which 12 people were brought from the Congo to pose for Western visitors. It was not the first ‘human zoo’, in which ‘the other’ was exhibited like an object: there was a long tradition of such displays. They became a regular feature at world exhibitions following those in Paris (1878), Amsterdam (1883) and Antwerp (1885). Non-Western peoples were dehumanized and framed as ‘primitive’, a strategy pursued by the West to legitimize colonialism. The Congo Pavilion attracted up to 15,000 visitors a day in 1885.

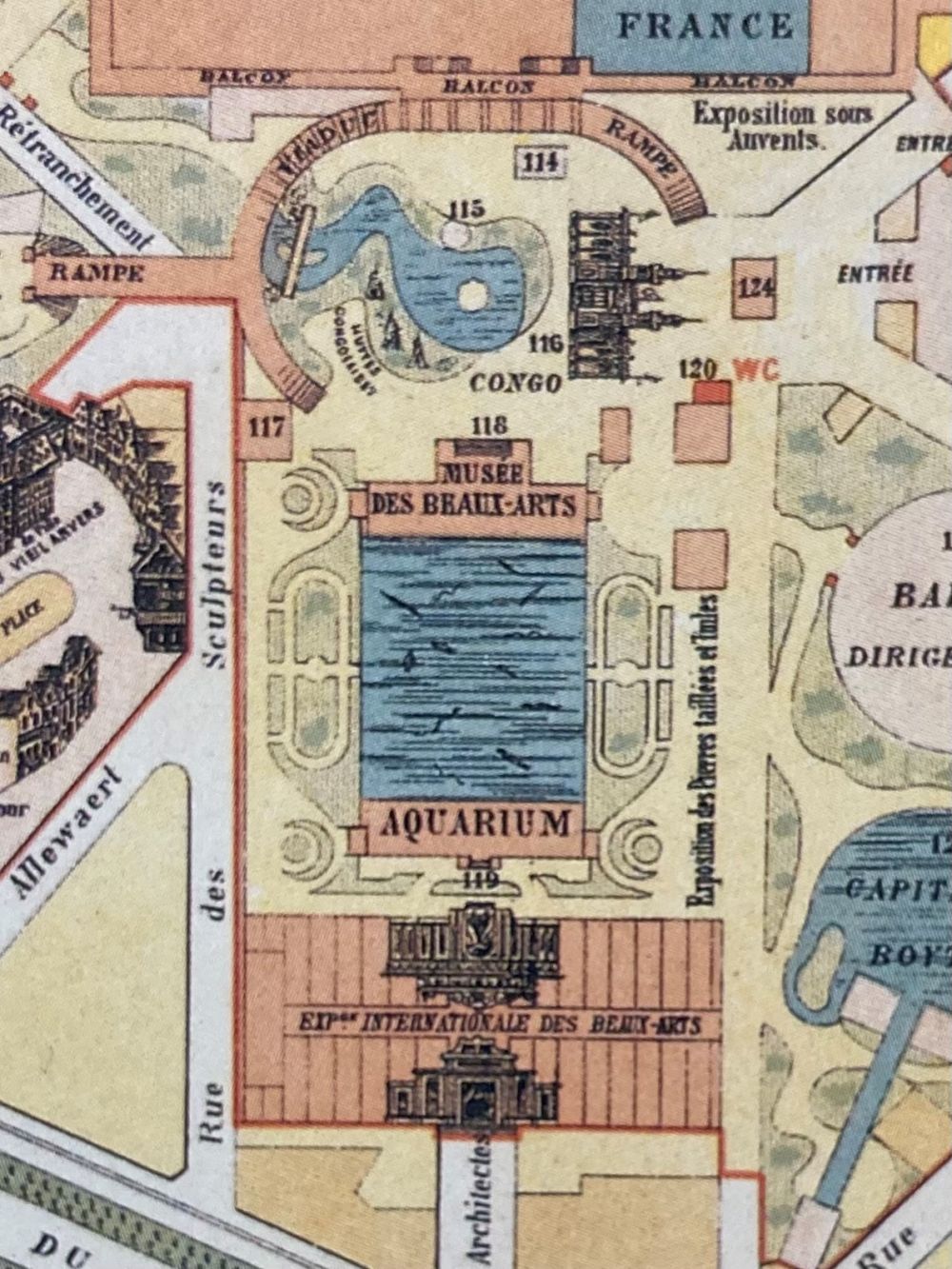

Fig. 1 – Detail from the visitor plan of the 1884 World Exhibition showing the area around the KMSKA - C.H. Bertels, Stadsarchief Antwerpen.

THE 1894 WORLD EXHIBITION

In 1894, Antwerp hosted another World Exhibition. The colonial section was set up on this occasion by the administrators of the Congo Free State. The colony was on the brink of bankruptcy at the time and Leopold II and his staff seized on the World Exhibition to whitewash the project’s image and as a propaganda opportunity. The enlarged colonial section consisted of a Congo Pavilion, a diorama and the reconstruction of a Congolese village, all located on the square in front of the KMSKA (what is now Leopold De Waelplaats).

The monumental Congo Pavilion (fig. 1, no. 116) offered a broad survey of colonial activities. Visitors could view items including Congolese art and everyday goods, colonial merchandise and work by contemporary Belgian artists done in Congolese ivory. A diorama (no. 117) immersed visitors in scenic views of the Congo painted by Henri Langerock (1830–1915). The organizers’ narrative was that Leopold II had liberated the Congo from ‘the Arab yoke’ – a line that the Belgian state would continue to promote for many years.

Instead of a single hut in front of the Congo Pavilion, this time there was an entire ‘Congolese village’ (no. 115), for which 144 Congolese people were brought over for public display. During the day they were made to perform activities for visitors, such as basket-weaving, metalwork, playing music and carving. At night, they slept in military barracks. These degrading conditions had an even worse dimension, as the project took a heavy physical toll on those involved: 44 of them fell ill as a result of the sea journey or their stay in Antwerp, and seven of them died. Bitio, Sabo, Isokoyé, Manguesse, Binda, Mangwanda and Pezo, all aged between 17 and 31, were buried in the city’s Schoonselhof cemetery.

THE KMSKA’S ROLE

hat relationship did the KMSKA have with the 1884 World Exhibition?

Fig. 4 – Detail of fig. 2 with the aquarium entrance - KMSKA

Fig. 2 – Frame from the temporary aquarium exhibit on the north - Th. Latin, Rijksmuseum.

The museum is labelled ‘Aquarium’ on the World Exhibition map (no. 118). A photograph of the imitation village (figs. 3–4) includes a sign on the right in front of the museum building identifying the entrance to this attraction. Tropical fish were displayed in the cellars in purpose-built tanks, the frames of which have been preserved (fig. 4). The KMSKA’s cellars thus formed part of the World Exhibition.

There were also plans to incorporate the upper galleries in the event: Baron de Vinck-de Winnezeele suggested displaying contemporary ivory sculptures there. But the museum board rejected the idea for logistical reasons, namely that the galleries the Baron had in mind were already being used to show engravings of works by Rubens. The ivories were exhibited instead in the Congo Pavilion.

The above account tells us that the initiative for involving the KMSKA in the World Exhibition came from outside. A letter from the museum to the City Council suggests that this was also the case with the aquarium, as it complains about the stench given off by the tanks and warns of leaks that could cause permanent damage.

The KMSKA did not, therefore, take the lead during the World Exhibition, which was organized by a Public Company supported by Antwerp City Council. The installation of the human zoo, moreover, was undertaken by the administrators of the Congo Free State, led by Leopold II. All the same, the event is part of the KMSKA’s history and we sincerely regret this painful episode. Any such inhumane project would obviously be firmly resisted nowadays.

3. UNEDIFYING STORIES

A museum tells stories. We allow the works of art we exhibit to interact with each other and we use a variety of channels to explain the collection. But telling stories means making choices and the first reflex is often to leave unedifying episodes untold.

Colonial history is manifested in the KMSKA’s collection too, but this is a narrative that has not previously been mapped out. What follows is intended as a first step in that direction. In some cases, items stored away for years in the museum depot are highlighted, while in others, objects that are displayed in the galleries are viewed through a different lens. This with the aim of drawing attention to the historical connections between the KMSKA, Antwerp and the Congo. In doing so, the negative side of this history will not be avoided.

Dupon’s Diana is the only one of the works cited below that is currently on display and has a text label. The work’s colonial background is already mentioned in the gallery. We refer to this text and to our guides to learn more about the context of the other works.

Fig. 5 – Detail of the De Keyser Gallery with the portrait of Leopold II - Nicaise De Keyser, KMSKA

CONGO FREE STATE (1885–1908)

Evidence of a colonial story can crop up in unexpected places. The De Keyser Room, our monumental staircase, is a case in point. It contains a large series of paintings by Nicaise De Keyser (1813–1887) glorifying Antwerp artists. A total of 175 different portraits are featured, and so the one of Leopold II (fig. 5), above the door on the landing does not immediately attract attention.

This particular image of the former king was not originally intended as colonial propaganda: De Keyser created his series in 1872 for the Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts, the original home of what became the KMSKA collection. Leopold II was not king of the Congo Free State at that time, merely that of Belgium. Nowadays, the monarch’s portrait is understandably identified in the public’s mind with his Congo policy. From 1885 to 1908, the Congo Free State was privately owned by Leopold II. His autocratic regime was marked by the use of violence and forced labour.

The king, his descendants and later the Belgian state all used art and culture to glorify the policy pursued there. Certain objects and artists in our collection are linked to those initiatives.

An example is Thomas Vinçotte (1850–1925), who sculpted numerous portraits of the Belgian monarch, including a bust that is now in the museum’s depot (fig. 6). Vinçotte also received several commissions for work condoning Leopold II’s Congo policy. In 1912, he designed the Monument to the Pioneers of the Belgian Congo for Cinquantenaire Park in Brussels. The work attempts to frame the colonial regime in the Congo – the reputation of which was already suspect – as a civilizing mission. The narrative that colonialism had enabled Belgium to liberate the Congolese from ‘the Arabs’ was reiterated.

The distinctive pair of chariots on the KMSKA roof are also Vinçotte’s work. In 1905, he collaborated with the sculptor Jules Lagae on another famous chariot group, namely the one crowning the central arcade of the triumphal arch in Cinquantenaire Park, Brussels. The monument was built on Leopold II’s initiative and was funded in part with money derived from the Congo.

Fig. 6 – Leopold II, King of the Belgians - Thomas Vinçotte, KMSKA

Fig. 7 – Art and Beauty - Emile Vloors, KMSKA

The artist Emile Vloors (1871–1952) also collaborated on the triumphal arch. In the 1920s, along with five other artists, he designed a series of 36 mosaics for the colonnade around the central edifice. Their theme was ‘the glorification of peaceful and heroic Belgium’. The artists did not depict the colonial atrocities that enabled the complex to be built.

Vloors devised the six scenes praising ‘the intellectual life’ of the nation in Cinquantenaire Park, of which Arts (inv. 3798, reading room) and Art and Beauty are shown by the KMSKA (fig. 7).

Leopold II’s likeness is a recurring element in a lesser-known part of the museum’s holdings, namely the medal collection, which was established in the early 20th century to commemorate important people and events. The medals are all currently stored in the depot.

Fernand Dubois’ medal of the sovereign is noteworthy in this context (fig. 8). it was struck in 1894 for the Congo Pavilion at that year's World Exhibition. To a contemporary viewer, the medal chiefly evokes the human zoo and its seven fatalities. This was evidently not the case when the KMSKA acquired the item as part of a culture of commemoration.

Fig. 8 – Leopold II, King of the Belgians. Struck for the Antwerp World Exhibition, the Congo section in 1894 - Fernand Dubois, KMSKA

Fig. 9 – Diana - Josuë Dupon, KMSKA

Some 336 tonnes of Congolese ivory passed through the port of Antwerp in 1900 alone. Leopold II promoted ivory as a sculptural material, as used by Josuë Dupon (1864–1935) for his Diana. The immense animal suffering and conflict that the ivory trade caused in the Congo is the gruesome flipside to Dupon’s elegant figurine.

Dupon belonged to a select group of sculptors in the king's entourage, He was a pupil of Vinçotte and a close friend of Lagae.

BELGIAN CONGO (1908–60)

The atrocities committed in the Congo Free State led to the Belgian state annexing the territory in 1908 under international pressure. Henceforward, the Colonial Ministry in Brussels would administer the region. A new Colonial Charter banned forced labour, but the practice continued nevertheless.

The heirs of Louis Franck (1868–1937), the second Colonial Minister, presented the KMSKA with his portrait (fig. 10) by the artist Walter Vaes (1882–1958).

Besides his political duties, Franck was actively involved in the operation of the KMSKA. He sat on the museum’s board of trustees and also belonged to societies like Kunst van Heden, which promoted contemporary art.

There are also several works dating from the era of the Belgian Congo that contain echoes of Congolese art. Earlier artists like Vinçotte and Dupon continued to pursue classical European ideals of beauty, but their successors frequently sought inspiration from other cultures. African masks triggered a major shift in Picasso’s visual language, for instance.

Fig. 10 – Louis Franck, Minister of State - Walter Vaes, KMSKA

Fig. 11 – Commemorative African Campaign Medal, 1914–18 - Oscar Jespers, KMSKA

The Congo offered Belgian artists an obvious gateway through which to find new forms. They did not even have to travel to Africa for them: since 1897, there had been a colonial museum in Tervuren – what later became the Royal Museum for Central Africa (RMCA). The institution was housed in a large new building in 1910 for the growing collection of masks, sculptures, weapons and utensils, many of them looted in the Congo. The sculptor Oscar Jespers (1887–1970) was inspired by visits to the collection. The hair of a wood sculpture by the Congolese Luba people, for instance, might have been drawn on for his Hooded Cloak (fig. 12).

The RMCA also featured work by Belgian artists, Jespers among them. In 1922, the Colonial Ministry – headed at the time by Louis Franck – asked him to sculpt Black Woman with Jug for the collection. It was an important commission for Jespers, who was paid 30,000 Belgian francs for the bronze sculpture – a huge amount for a work of art at the time. The money came from the Congolese treasury. The Hooded Cloak, by comparison, had sold for 6,500 Belgian francs.

The painter Floris Jespers (1889–1965), brother of the sculptor, visited the Congo several times in the 1950s. This triggered a fundamental change in his later work, in which a key role is played by Congolese figures like African Woman (fig. 14). His new work was met with widespread applause in Belgium. Jespers also received several commissions for murals in public buildings in colonial Congo. The Colonial Ministry ordered a large painting from him, lastly, for the Congo Pavilion at Expo ’58, the final Belgian World Exhibition (1958) to feature a human zoo.

Fig. 14 – African Woman - Floris Jespers, KMSKA

Fig. 15 – Head of a Woman – Anonymous sculptor - Anonieme meester, KMSKA

Floris Jespers’ letters betray the sense of superiority towards the Congolese people that was common among colonials. All the same, he considered the Congo and its art to be part of his artistic personality. He appropriated the country: literally so. According to a newspaper article published at the time of his death, Jespers was buried at Antwerp’s Schoonselhof cemetery in Congolese soil brought over specially at his request.

There are two African items, lastly, that unexpectedly form part of the KMSKA collection (fig. 15 and inv. 3241, depot). They were bequeathed by the heirs of Camiel Huysmans (1871–1968), former Socialist mayor of Antwerp, who visited the Congo in 1951. Huysmans might have brought this ebony sculpture of a woman’s head back with him on that occasion. It is of a type produced in large quantities for the European market.

Research: Koen Bulckens

We were only able to complete this work with the valuable input of a number of experts. We are grateful in this regard to Dr Bambi Ceuppens (KMMA), Leen De Jong, Prof. Idesbald Godeeris (KUL), Prof. Ulrike Müller (UA), Dr Els De Palmenaer (MAS), Guy Poppe and Prof. Ilja Vandamme (UA).

Special thanks are due to Prof. Emeritus Frans Buelens (UA), who combed through our list of donors, Nadia Nsayi (KMMA), whose close reading of the Dutch version of this text revealed crucial blind spots in our account of the 1894 World Exhibition, and Prof. Guy Vanthemsche (VUB), who helped us to articulate certain historical dynamics more sharply.

CONSULTED LITERATURE

Inventaris Onroerend Erfgoed (online database of Flemish architectural heritage)

Belgian Lower House of Parliament, Bijzondere commissie belast met het onderzoek over Congo-Vrijstaat (1885-1908) en het Belgisch koloniaal verleden in Congo (1908-1960), Rwanda en Burundi (1919-1962), de impact hiervan en de gevolgen die hieraan dienen gegeven te worden, report 17 July 2020.

Els De Palmenaer (ed.), 100 x Congo. Een eeuw Congolese kunst in Antwerpen (exh. cat. Museum aan de Stroom, Antwerp), Kontich: BAI, 2020.

Leen De Jong (ed.), Schenkingen aan het Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen. 1818–2018, Ghent: Lannoo, 2020.

José Boyens, Oscar Jespers, beeldhouwer en tekenaar, 1887–1970. Met een geïllustreerde, kritische en gedocumenteerde catalogus van de beeldhouwwerken, Wormerveer: Uitgeverij Noord-Holland, 2013

Bram Van Oostveldt and Stijn Bussels, ‘De Antwerpse wereldtentoonstelling van 1894 als ambigu spektakel van de moderniteit’, Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 125 (2012), 4–19.

Guy Vanthemsche, Belgium and the Congo, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Leen De Jong et al., Het Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen. Een geschiedenis 1810–2007, Oostkamp: Stichting Kunstboek, 2008.

Frans Beulens, Congo 1885–1960. Een financieel-economische geschiedenis, Berchem: Epo, 2007.

Maarten Couttenier, Congo tentoongesteld. Een geschiedenis van de Belgische antropologie en het museum van Tervuren (1882-1925), Leuven: Acco, 2005.

Jean F. Buyck, Retrospectieve Floris Jespers (exh. cat. Museum voor Moderne Kunst, Ostend), Antwerp: Pandora, 2004.

Jacqueline Guisset, Congo en de Belgische Kunst, 1880–1960 (exh. cat. Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren), Tournai: Renaissance du livre, 2003.

Mandy Nauwelaerts (et al.), De panoramische droom. Antwerpen en de wereldtentoonstellingen 1885, 1894, 1930 (exh. cat. Bouwcentrum, Antwerp): Antwerp 1993 VZW, 1993.

Jean Stengers, Combien le Congo a-t-il coûté à la Belgique, Gembloux: J. Duculot, 1957.

Fernand Khnopff, ‘the Revival of Ivory Carving in Belgium’, The Studio 4 (1895), 150–51.