Hidden signatures and dates, later reworkings and overpaintings: James Ensor continues to surprise

An article by Annelies Ríos-Casier

Artists are often known for their creativity and originality, but how are some of these works actually created? Sometimes a painting tells a hidden story of reworking and experimentation that makes us look at the work differently. During the creative process, an artist may change their mind, modify parts of a painting, or even reuse a finished work as the basis for something new.

This is also true of James Ensor, one of Belgium's most important modernist painters and one of the highlights of the KMSKA collection. Research conducted as part of the KMSKA's Ensor Research Project, in collaboration with the University of Antwerp and an international research team (Molab – Iperion), shows that Ensor reworked his paintings in various ways. This ranged from completely repainting compositions to subtle touch-ups and even transforming works by other artists into his own creations. Five paintings by Ensor from different collections were examined in depth and illustrate concretely how he worked, sometimes subtly but often radically.

Modern and traditional research techniques make it possible to uncover hidden information in paintings. Ultraviolet light reveals details on the surface, while infrared light penetrates deeper and makes signatures visible. X-rays allow researchers to see through a painting and detect hidden compositions. Advanced methods such as Macro X-Ray Fluorescence (MA-XRF) even allow researchers to look beneath the paint layers and create digital reconstructions of what remains hidden to the naked eye. This provides insight into all the layers of a painting, enabling researchers to determine which paint layers are older and to see how a work has been altered over time.

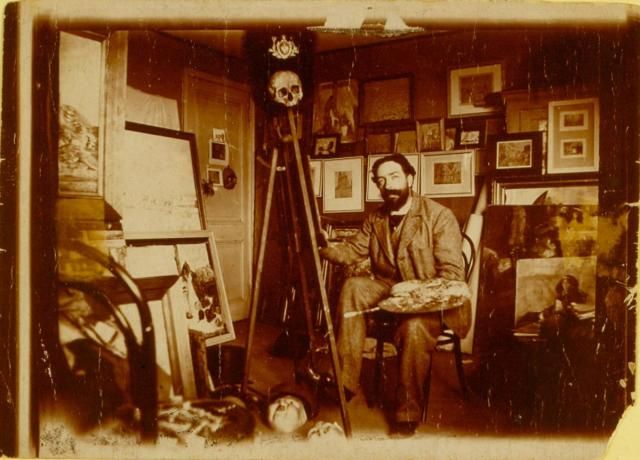

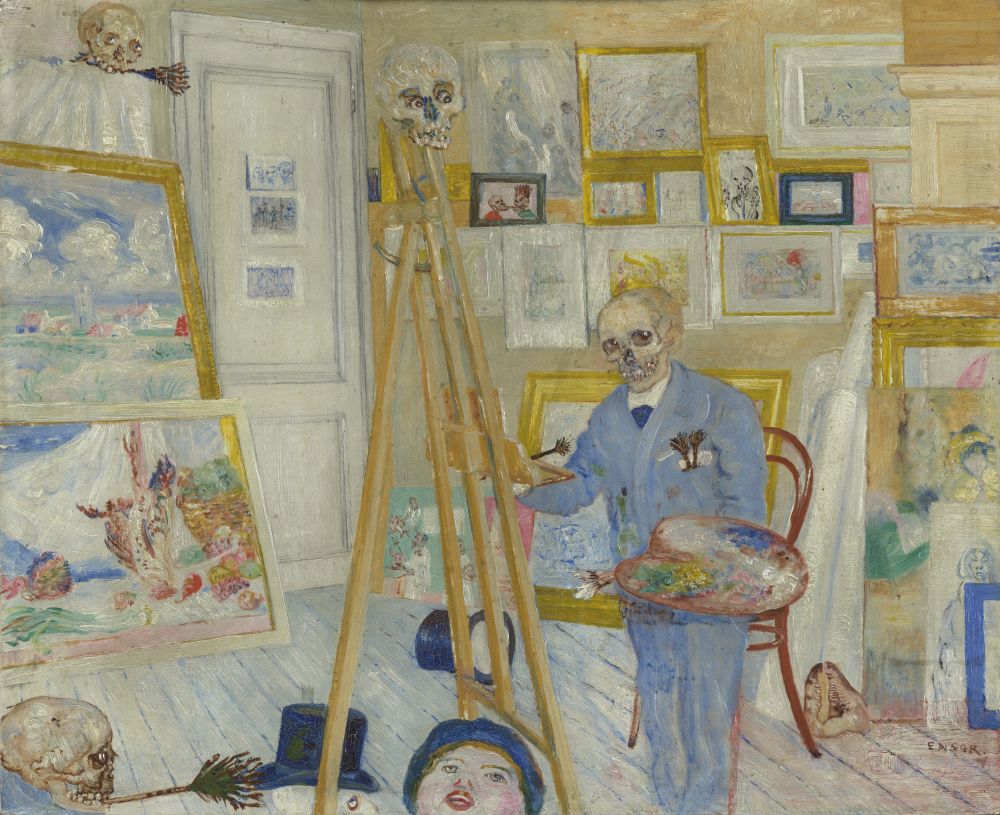

The Skeleton Painter

The five paintings examined demonstrate in different ways how Ensor edited and transformed his work. In The Skeleton Painter (1896) from the KMSKA collection, pentimenti were discovered—that is, changes made by an artist while a work is still in development. The painting is based on a photograph of Ensor in his studio, but the final result differs from the photograph. Infrared images show that Ensor initially followed the photograph closely while sketching, but later chose to deviate from it while painting: he transformed his self-portrait into a skull and depicted himself standing rather than sitting.

The Skeleton Painter

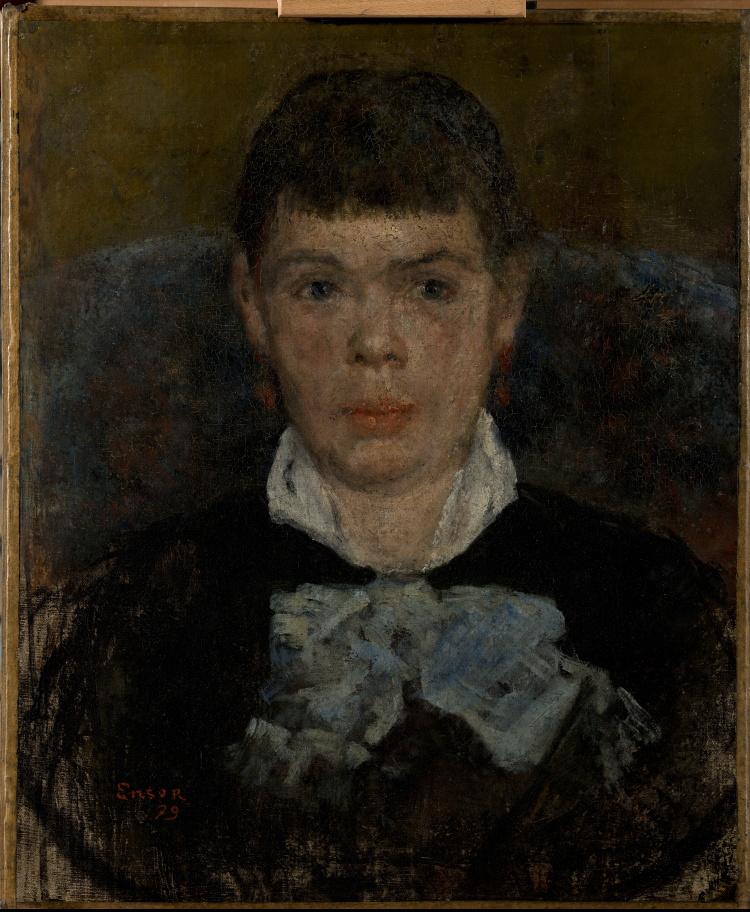

Woman with Upturned Nose

In Woman with Upturned Nose (1879), we see a different type of reworking. Years later, Ensor made subtle adjustments: small touches of paint to the eyes, ears, and lips, executed with materials he only began using around 1887, as well as traces of coloured pencil characteristic of his later style. This indicates that the painting was reworked at a later date, probably to freshen it up before it was sold or exhibited.

Woman with Upturned Nose

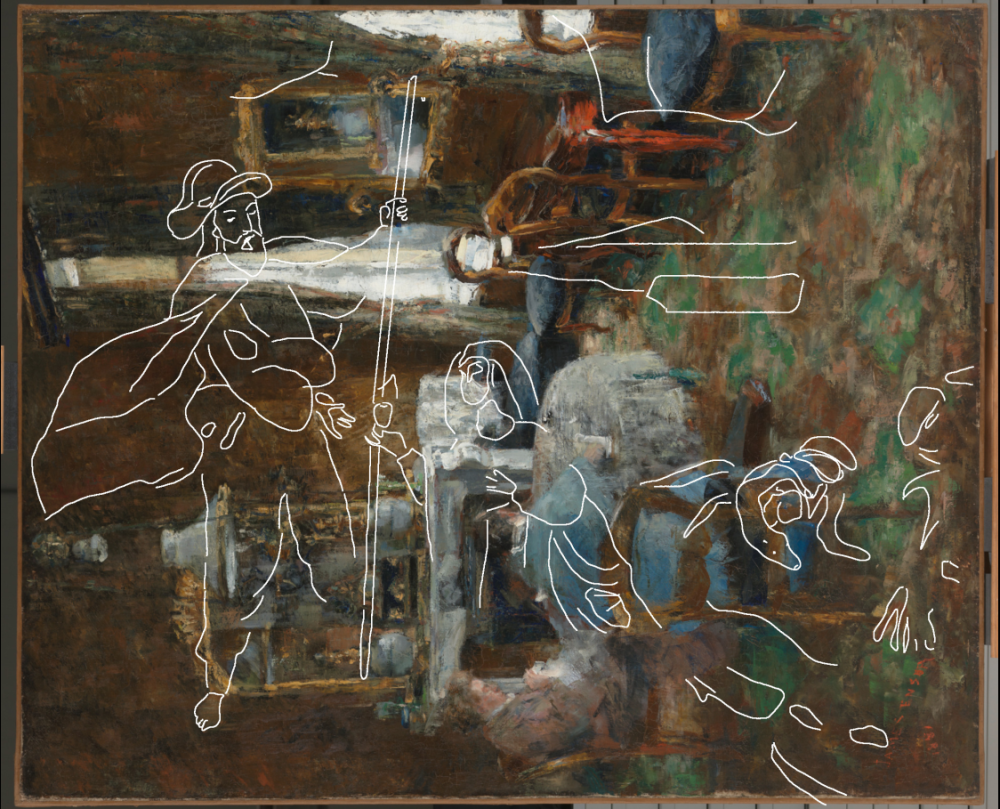

the Bourgeois Salon

In The Bourgeois Salon (1881), also from the KMSKA collection, Ensor recycled his canvas, meaning that he completely painted over an existing composition to create a new work. Beneath the visible scene, a completely different composition emerges: a man with a beard, hat, cape, and staff stands next to a kneeling figure who is handing over an object (perhaps an apple?), while the background remains indistinct. Ensor used this technique regularly, especially during his early period. He may have been dissatisfied with the original work, or he may have reused his canvases for practical or financial reasons.

The Bourgeois Salon

Self-Portrait with Flower Hat

The famous Self-Portrait with Flower Hat from Mu.ZEE in Ostend was painted in two phases. Ensor began with a realistic self-portrait and only added the flowered hat, feather, and other details years later, around 1888. These additions, or metamorphosis, gave the work a strikingly more feminine and self-assured appearance. Although he dated the work 1883, Ensor deliberately remained vague about the fact that it had been created in two phases. This also reveals a clear contrast between the early, darkly painted self-portrait and the later, colourful elements of the hat and feather, both in terms of technique and style. In the lower right corner, researchers discovered two overpainted signatures and dates, both bearing the date “1885”. This suggests that the original portrait may have been painted later than initially assumed. It seems that Ensor deliberately backdated the work to 1883, possibly to emphasise his reputation as an innovative artist and to demonstrate that he was experimenting with this type of painting at an early stage.

Self-Portrait with Flower Hat

The Adoration of the Shepherds

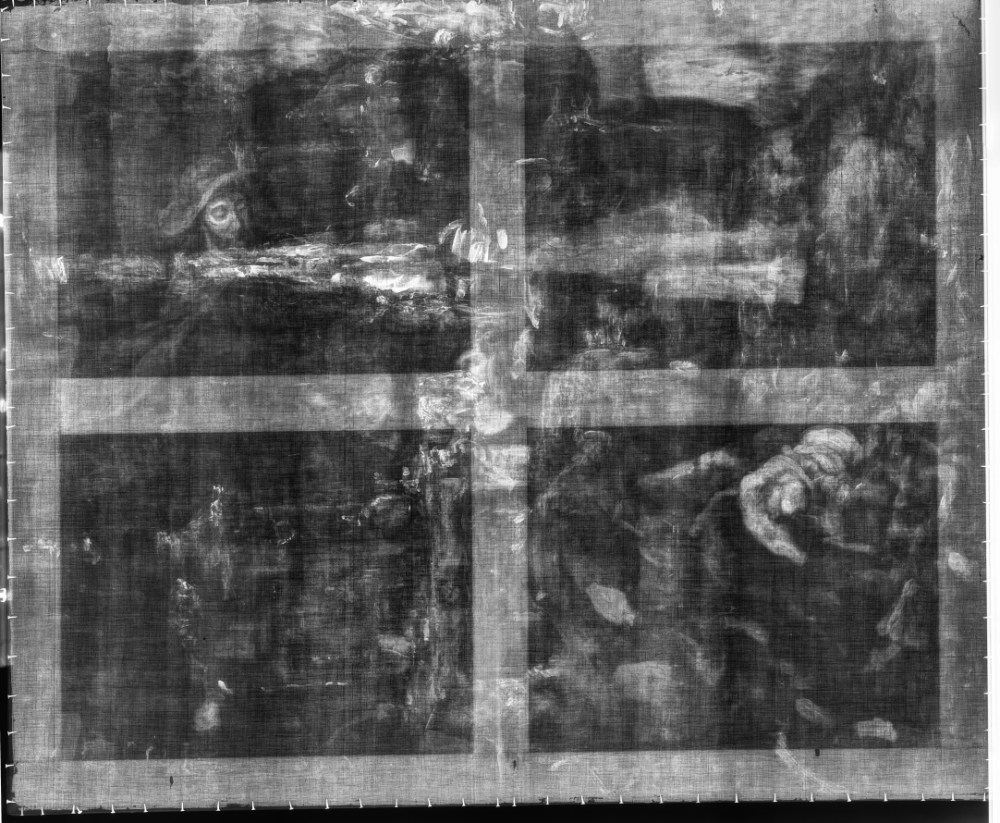

Finally, The Adoration of the Shepherds (KMSKB) shows how Ensor appropriated an existing work by another artist and transformed it into his own composition. The original work, by an unknown nineteenth-century painter, depicted a detailed and finely painted peasant scene. Ensor reworked this scene by applying thick brushstrokes and transforming the peasants’ clothing into royal robes. The composition was also altered: the table around which the peasants were seated was transformed into the manger in which the baby Jesus lies. Ensor’s additions remain clearly recognisable, especially in raking light, where the impasto—thickly applied paint—is clearly visible.

The Adoration of the Shepherds

A complex story

This research emphasises that much of the rich artistic narrative lies beneath the surface. The ways in which Ensor and his contemporaries created and reworked their works over time shed light on their studio practices, intentions, and the artistic developments of their era. Ultimately, this research reveals that art is not a static end product, but a dynamic, constantly evolving process. Every brushstroke, every revision, and every hidden composition contributes to a complex narrative.

This research was supported by the Research Foundation – Flanders (PhD Fellowships in Fundamental Research, no. 1183125N, Annelies Rios Casier) and by the EU’s Horizon 2020 programme (IPERION HS, no. 871034), which enabled measurements for the BelMod project in 2022. We would also like to thank Mu.ZEE and the KMSKB for making their collections available for research.