The art of collecting

The beginning of a collection

1382: Guild of St Luke

In 1382 Antwerp’s painters, sculptors, stained-glass artists, embroiderers, goldsmiths and silversmiths joined together in the Guild of St Luke. Notable names like Jan Brueghel (1602), Otto van Veen (1603) and Cornelis de Vos (1619) all feature in the membership rolls as well as in the KMSKA’s collection.

Guild members held their meetings and festivities at the ‘Painter’s Chamber’, which they also decorated with examples of their work. In 1556, for instance, Frans Floris painted Luke, the guild’s patron saint, to adorn the chamber and in 1633, Rubens presented it with his Holy Family with a Parrot.

Heilige Lucas - Frans Floris, KMSKA

De Heilige Familie met de papegaai - Peter Paul Rubens, KMSKA

1663: founding of the Academy

David Teniers the Younger founded an academy under the auspices of the Guild of St Luke to offer young artists a comprehensive curriculum of humanities, sciences and fine arts. They were taught the principles of perspective and architecture and drew from plaster casts and life models.

A need swiftly arose for extra space and so the guild and its academy moved as early as 1664 to a wing of the commercial exchange (Handelsbeurs). The magnificent interior design was provided by Jacob Jordaens, Theodor Boeijermans and many other members too.

The Guild of St Luke was disbanded in 1773 and its art collection was inherited by the academy.

Antwerp, Nourishing the Painters - Theodor Boeijermans

1794: French looting

French revolutionary troops occupied the city in 1794 and closed down its churches and abbeys. They stripped the religious institutions of their artworks, the most important of which were shipped off to Paris where they were exhibited at the Louvre along with art stolen from other countries.

Napoleon founded the Antwerp museum by imperial decree on 5 May 1810 and installed the academy and its collection at the vacant Franciscan monastery in Mutsaardstraat. The church and part of the monastery were set up as public galleries and the academy is still located there today.

1815: stolen artworks returned

The Flemish masters made their way home again after the Battle of Waterloo. A substantial proportion of the looted works arrived in Antwerp by train on 5 December 1815. Twenty-six paintings – mostly by Rubens – were placed in the recently founded academy museum.

The 1817 catalogue lists 127 items – a small collection, but of the highest quality. The nucleus comprised works from the second half of the 16th century and the 17th century, with Rubens as the crowning glory.

1840: generous knight

The collection received a major boost in 1840, when the art collector and knight Florent van Ertborn bequeathed artistic gems by the likes of Jan van Eyck, Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Memling and Jean Fouquet. The former mayor of Antwerp left 144 paintings to the museum in his native city.

Van Ertborn’s legacy corrected the earlier bias of the collection towards 16th and 17th-century works, by enriching it with masterpieces from the 14th, 15th and early 16th centuries. It was one of the largest bequests in the museum’s history.

1851: academicians’ museum

The museum and academy took the first steps in 1850 towards building a collection of contemporary art. The Academy founded an ‘Academic Corps’ and the leading artists who joined were required to donate both a work of art and a portrait. The ‘academicians’ museum’ as it was called steadily developed into a genuine collection of modern art, with over a hundred paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints. Important artists like Antoine Wiertz, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, August Kiss, Alexandre Cabanel and William Adolphe Bouguereau were all given a prominent place in the ‘academic gallery’.

Cleopatra - Alexandre Cabanel, KMSKA

1873: a new department for modern art

The museum purchased its first work by living artists at the Antwerp Salon in 1873. The new modern masters department was supplemented by six paintings by artists with links to the academy. From then on, the museum would regularly buy art at official salons, with preference given to work of a rather conservative and patriotic character.

A true museum of art for Antwerp

1875: dreams of a new museum

The upshot of all this growth was predictable: the academy museum began to run out of space. Climate control and fire safety were no longer fit for purpose either. The city daydreamed out loud about a new museum of fine arts and, having weighed up all the options, decided in 1875 to build a museum on recently cleared land in the Antwerp South district, where the Spanish fortress had once stood. When the Belgian state also backed the project, there was nothing standing in the city’s way.

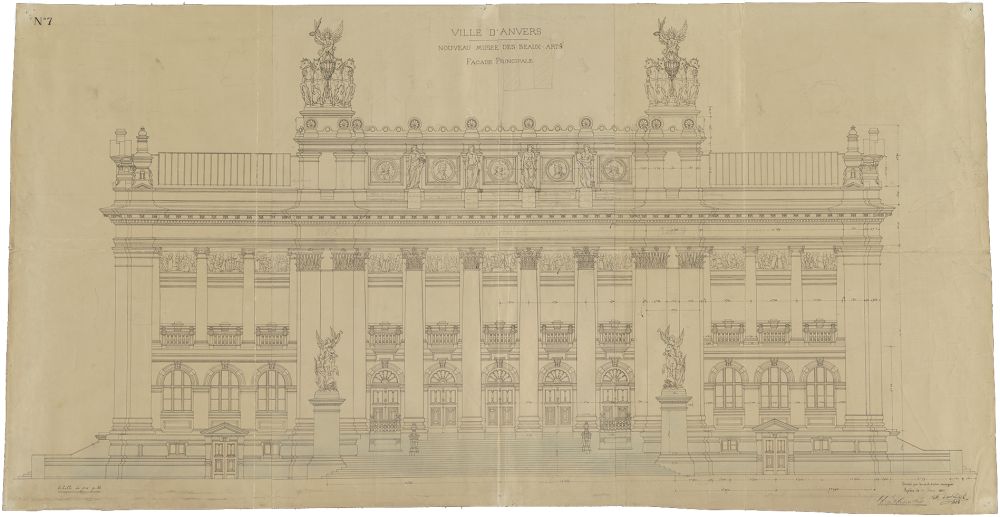

Construction plans drawn up by the architects Jean Jacques Winders and Frans Van Dijk. - KMSKA archives - Archief KMSKA

1877: ‘Competition to Establish a Museum of Fine Arts’

Antwerp City Council held a competition to design a new museum but none of the entries was entirely convincing. The city eventually invited the young architects Jean Jacques Winders and Frans Van Dijk to combine their respective designs in a single plan. They took everything into account, from a sense of grandeur to functionality and security.

The new museum would be a standalone structure with galleries located high above the ground. This ensured a safe distance in terms of fire risk between the art and the nearby residential neighbourhood, while potential flooding would not affect the exhibits either. The architects went even further, installing a fire and bomb-proof basement in the middle of the building.

First and foremost, it was a daylight museum, with a variety of lighting angles to show sculpture and paintings to the best effect. Windows in the walls lit the statues on the first floor, with skylights for the paintings on the upper storey.

1890: opening

After six years of construction work, the new museum opened to the public on 11 August 1890 with a large-scale celebration attended by Mayor Leopold De Wael and the members of the City Council. The event began with a ceremony at the Town Hall with various dignitaries, painters and sculptors, following which the guests walked to the museum in a colourful procession. On arrival, they were served a sumptuous banquet in the new building.

1894: a shameful chapter in the history of the museum square: the World Exhibition

In 1894, Antwerp hosted a second World Exhibition. The colonial section was set up on this occasion by the administrators of the Congo Free State. The colony was on the brink of bankruptcy at the time and Leopold II and his staff seized on the World Exhibition to whitewash the project’s image and as a propaganda opportunity. The enlarged colonial section consisted of a Congo Pavilion, a diorama and the reconstruction of a Congolese village, all located on the square in front of the KMSKA (what is now Leopold De Waelplaats). 144 Congolese people were brought over for public display. During the day they were made to perform activities for visitors, such as basket-weaving, metalwork, playing music and carving. At night, they slept in military barracks. These degrading conditions had an even worse dimension, as the project took a heavy physical toll on those involved: 44 of them fell ill as a result of the sea journey or their stay in Antwerp, and seven of them died. Bitio, Sabo, Isokoyé, Manguesse, Binda, Mangwanda and Pezo, all aged between 17 and 31, were buried in the city’s Schoonselhof cemetery.

1905: the triumph of art and Art of Today

G. van Bergen contractors employed a dozen men to hoist Thomas Vinçotte’s pair of chariots to the roof. With a team of two horses and a charioteer apiece, they were intended to symbolize the triumph of art and have been the emblem of the museum ever since they were installed.

The Antwerp Franck family plays an important role in the growth of the modern art collection. As the central figure François Franck, establishes the association Kunst van Heden (Art of Today) in 1905 and Friends of Modern Art in 1925. He encouraged everyone in his network to buy and donate art to the museum. Through purchases and donations, the museum enriched its collection with important modern works of art: from Belgian Impressionism to Flemish Expressionism. With, among others, James Ensor and Gustave Van De Woestyne, Ossip Zadkine and Marc Chagall.

War and renovation

1914: the First World War

The museum took immediate and drastic action on the outbreak of the First World War. The building and its gardens were closed and staff took all the artworks down into the bomb-proof basement. Churches and other public institutions were also able to store their artistic treasures there. It was briefly considered that a field hospital should be installed in the now empty galleries, but in the end, the staff took the opportunity to refurbish the interior. Just in time, because the German occupier gave permission for the museum to reopen in 1915. In the event, only the modern art department opened its doors again, with the old masters remaining safely in the basement.

1925: museum too small

The development of the building has always been closely linked to the growth of the museum’s collection. In less than 40 years of its opening, the museum was already too small and four internal courtyards were covered over to create additional gallery space. The interior windows were removed and the galleries now began to look like a modern museum space.

1940: the museum during the Second World War

A secure basement needs a fully developed contingency plan to be truly effective. Right from the outset, the museum was designed with trapdoors in the floor of the central galleries to allow works of art to be hoisted safely into the basement in an emergency. When the Second World War broke out, museum staff lowered numerous paintings into the underground shelter once again.

Not that this meant there was no longer any threat. At 9.45 in the morning of 13 October 1944, the very first German flying bomb landed on Antwerp, right next to the museum. Thirty-two people were killed and the museum and some of its artworks were badly damaged. The glass roofs shattered. It took years to repair the damage suffered during the war.

As the threat of war intensified, museum staff began to lower paintings into the secure basement. - KMSKA Archives

V-bomb strike on the corner of Karel Rogierstraat and Schildersstraat. - KMSKA Archives

The first blockbuster

1976–77: Rubens Year

In 1977 Antwerp staged a grandiose ‘Rubens Year’ celebration in which the city’s businesses and institutions queued up to take part. The KMSKA obviously had to be involved too, but the building had fallen into disrepair and was in no state to welcome modern visitors properly. There was no electric lighting in the galleries, for instance. Large-scale renovations began on 3 August 1976.

One year later, the museum was ready for the most extensive and varied of all the Rubens Year initiatives. The public responded enthusiastically to both the exhibition and the refurbishment. A total of 625,000 visitors were drawn to the museum, making the event a genuine blockbuster, even by today’s standards.

The horses were allowed off the roof during the renovation in 1976 - KMSKA Archives

Queuing for the Rubens Exhibition in 1977. - KMSKA Archives

1989: Rik Wouters

In 1989, Baron Ludo van Bogaert and his wife Marie-Louise Sheid donated their substantial collection of works by Rik Wouters to the KMSKA: 13 paintings, eight sculptures and 36 drawings and watercolours. In addition to the world’s most important Ensor collection, the museum now boasts the biggest Wouters collection too.

1999: A city square with art

The museum stands on something of an island visually, so the City Council had the square in front of it redesigned by the architects Paul Robbrecht and Hilde Daem in collaboration with Marie-José van Hee. A sculpture by Josuë Dupon and four heads by Rodin taken from the former Loos monument, offer a taste of the art inside. A bench by Ann Demeulemeester invites you to meet, Deep Fountain by Cristina Iglesias to meditate.

Forward-looking grandeur

2003: a master plan for the KMSKA

The Flemish Government Architect bOb Van Reeth issued an open call to draw up a master plan for the KMSKA. The brief was to update the museum building in keeping with 21st-century needs.

In 2006, KAAN Architects of Rotterdam were commissioned to go ahead with the plan. The firm opted for an impressive makeover from a 19th-century museum to one firmly oriented to the future.

2011: large-scale renovation

The most recent renovation began in the autumn of 2011 to put KAAN Architects’ master plan into practice. The historic building has regained its grandeur, while a brand-new museum volume has been inserted at the core. The spatial experience and play of light in the new building are overwhelming.